1. Spring Batch 介绍

在企业域环境中针对关键环境进行商业操作的时候,有许多应用程序需要进行批量处理。这些业务运营包括:

-

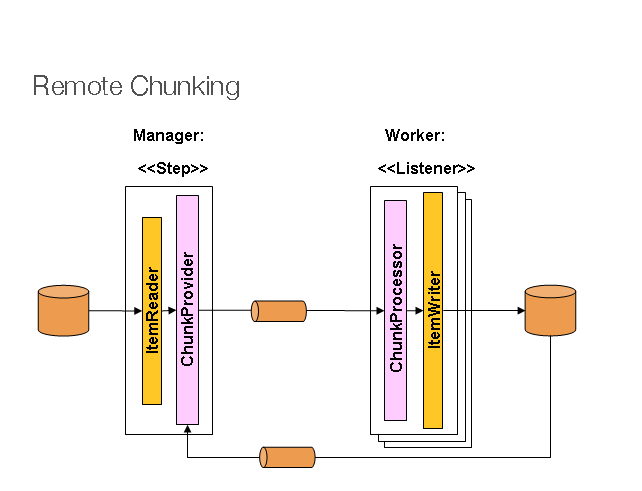

无需用户交互即可最有效地处理大量信息的自动化复杂处理。这些操作通常包括基于时间的事件 (例如,月末统计计算,通知或者消息通知)。

-

在非常大的数据集中重复处理复杂业务规则的定期应用(例如,保险利益确定或费率调整)。

-

整合从内部或者外部系统中收到的信息,这些信息通常要求格式,校验和事务范式处理到记录系统中。 批处理通常被用来针对企业每天产生超过亿万级别的数据量。

Spring Batch是一个轻量级的综合性批处理框架,可用于开发企业信息系统中那些至关重要的数据批量处理业务。 Spring Batch构建了人们期望的Spring Framework 特性(生产环境,基于 POJO 的开发和易于使用), 同时让开发者很容易的访问和使用企业级服务。Spring Batch 不是一个自动调度运行框架。在市面上已经有了很多企 业级和开源的自动运行框架(例如 Quartz,Tivoli, Control-M 等)。 Spring Batch 被设计与计划任务和调度程序一同协作完成任务,而不是替换调度程序。

Spring Batch 提供了可重用的功能,这些功能被用来对大量数据和记录进行处理,包括有日志/跟踪(logging/tracing), 事务管理(transaction management),作业处理状态(job processing statistics),作业重启(job restart), 作业跳过(job skip)和资源管理(resource management)。 此外还提供了许多高级服务和特性, 使之能够通过优化(optimization ) 和分片技术(partitioning techniques) 来实现极高容量和性能的批处理作业。 Spring Batch 能够简单(例如,将文件读入到数据库中或者运行一个存储过程)和复杂(例如,在数据库之间对海量数据进行移动或转换等) 情况下都能很好的工作。 可以在框架高度扩展的方式下执行大批量的作业来处理海量的信息。

1.1. 背景

在开源项目及其相关社区把大部分注意力集中在基于 web 和 微服务体系框架时框架中时,基于 Java 的批处理框架却无人问津, 尽管在企业 IT 环境中一直都有这种批处理的需求。但因为缺乏一个标准的、可重用的批处理框架导致在企业客户的 IT 系统中 存在着很多一次编写,一次使用的版本,以及很多不同的内部解决方案。

SpringSource (现被命名为 Pivotal) 和 Accenture(埃森哲)致力于通过合作来改善这种状况。 埃森哲在实现批处理架构上有着丰富的产业实践经验,SpringSource 有深入的技术开发积累, 背靠 Spring 框架提供的编程模型,意味着两者能够结合成为默契且强大的合作伙伴,创造出高质量的、市场认可的企业级 Java 解决方案, 填补这一重要的行业空白。两家公司都与许多通过开发基于Spring的批处理架构解决方案解决类似问题的客户合作。 这提供了一些有用的额外细节和实际约束,有助于确保解决方案可以应用于客户提出的现实问题。

埃森哲为Spring Batch项目贡献了以前专有的批处理体系结构框架,以及提供支持,增强功能和现有功能集的提交者资源。 埃森哲的贡献基于几十年来在使用最新几代平台构建批量架构方面的经验:COBOL / Mainframe,C / Unix以及现在的Java / Anywhere。

埃森哲与SpringSource之间的合作旨在促进软件处理方法,框架和工具的标准化, 在创建批处理应用程序时,企业用户可以始终如一地利用这些方法,框架和工具。希望为其企业IT环境提供标准的, 经过验证的解决方案的公司和政府机构可以从 Spring Batch 中受益。

1.2. 使用场景

一般的典型批处理程序:

-

从数据库,文件或队列中读取大量记录。

-

以某种方式处理数据。

-

以修改的形式写回数据。

Spring Batch自动执行此基本批处理迭代,提供处理类似事务的功能,通常在脱机环境中处理,无需任何用户交互。 批处理作业是大多数 IT 项目的一部分,Spring Batch 是唯一提供强大的企业级解决方案的开源框架。

业务场景

-

周期提交批处理任务

-

同时批处理进程:并非处理一个任务

-

分阶段的企业消息驱动处理

-

高并发批处理

-

失败后的手动或定时重启

-

按顺序处理任务依赖(使用工作流驱动的批处理插件)

-

部分处理:跳过记录(例如,回滚)

-

全批次事务:因为可能有小数据量的批处理或存在存储过程/脚本中

技术目标

-

批量的开发者使用 Spring 的编程模型:开发者能够更加专注于业务逻辑,让框架来解决基础的功能

-

在基础架构、批处理执行环境、批处理应用之间有明确的划分

-

以接口形式提供通用的核心服务,以便所有项目都能使用

-

提供简单的默认实现,以实现核心执行接口的“开箱即用”

-

通过在所有层中对 Spring 框架进行平衡配置,能够实现更加容易的配置,自定义和扩展服务。

-

所有存在的核心服务应该能够很容易的在不同系统架构层进行影响的情况进行替换或扩展。

-

提供一个简单的部署模块,使用 Maven 来进行编译的 JARs 架构,并与应用完全分离。

1.3. Spring Batch 体系结构

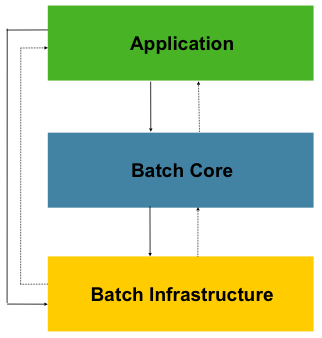

Spring Batch 设计的时候充分考虑了可扩展性和各类最终用户。 下图显示了 Spring Batch 的架构层次示意图,这种架构层次为最终用户开发者提供了很好的扩展性与易用性。

这个层级体系结构高亮显示了 Spring Batch 的 3 个主要组件:应用(Application),核心(Core)和 基础架构(Infrastructure)。

应用层包含了所有的批量作业和开发者使用 Spring Batch 写的所有自定义代码。批量核心层包含了所有运行和控制批量作业所需必要的运行时类。

同时还包括了有 JobLauncher, Job, 和 Step。应用层和核心层都构建在基础架构层之上。

基础架构层包含了有 读(readers)和 写(writers )以及服务(services)。例如有针对服务使用, RetryTemplate。

基础架构层的这些东西,这些能够被应用层开发(readers 和 writers,

例如 ItemReader 和 ItemWriter)和批量核心框架(例如,retry,这个是核心层自己的库)所使用。

简单的来说,基础架构层为应用层和批量核心层提供了所需要的的基础内容,是整个 Spring Batch 的基础。我们针对 Spring Batch 的开发绝大部分情况是在应用层完成的。

1.4. 一般批量处理的原则和使用指引

下面是一些关键的指导原则,可以在构批量处理解决方案可以参考。

-

请记住,通常批量处理体系结构将会影响在线应用的体系结构,同时反过来也是一样的。 在你为批量任务和在线应用进行设计架构和环境的时候请尽可能的使用公共的模块。

-

越简单越好,尽量在一个单独的批量应用中构建简单的批量处理,并避免复杂的逻辑结构。

-

尽量的保持存储的数据和进程存储在同一个地方(换句话说就是尽量将数据保存到你程序运行的地方)。

-

最小化系统资源的使用,尤其针对 I/O。尽量在内存中执行尽可能多的操作。

-

检查应用的 I/O(分析 SQL 语句)来避免不必要的的物理 I/O 使用。特别是以下四个常见的缺陷(flaws)需要避免:

-

在数据可以只读一次就可以缓存起来的情况下,针对每一个事务都来读取数据

-

多次读取/查询同一事务中已经读取过的数据

-

产生不必要的表格或者索引扫描

-

在 SQL 查询中不指定 WHERE 查询的值

-

-

在批量运行的时候不要将一件事情重复 2 次。例如,如果你需要针对你需要报表的数据汇总,请在处理每一条记录时使用增量来存储, 尽可能不要再去遍历一次同样的数据。

-

为批量进程在开始的时候就分配足够的内存,以避免在运行的时候再次分配内存。

-

总是将数据完整性假定为最坏情况。对数据进行适当的检查和数据校验以保持数据完整性(integrity)。

-

可能的话,请实现内部校验(checksums )。例如,针对文本文件,应该有一条结尾记录, 这个记录将会说明文件中的总记录数和关键字段的集合(aggregate)。

-

尽可能早地在模拟生产环境下使用真实的数据量,以便于进行计划和执行压力测试。

-

在大数据量的批量中,数据备份可能会非常复杂和充满挑战,尤其是你的系统要求不间断(24 - 7)运行的系统。 数据库备份通常在设计时就考虑好了,但是文件备份也应该提升到同样的重要程度。如果系统依赖于文本文件, 文件备份程序不仅要正确设置和形成文档,还要定期进行测试。

1.5. 批量处理策略

为了帮助设计和实现批量处理系统,基本的批量应用是通过块和模式来构建的, 同时也应该能够为程序开发人员和设计人员提供结构的样例和基础的批量处理程序。

当你开始设计一个批量作业任务的时候,商业逻辑应该被拆分一系列的步骤,而这些步骤又是可以通过下面的标准构件块来实现的:

-

转换应用程序(Conversion Applications): 针对每一个从外部系统导出或者提供的各种类型的文件, 我们都需要创建一个转换应用程序来讲这些类型的文件和数据转换为处理所需要的标准格式。 这个类型的批量应用程序可以是正规转换工具模块中的一部分,也可以是整个的转换工具模块(请查看:基本的批量服务(Basic Batch Services))。

-

校验应用程序(Validation Applications): 校验应用程序能够保证所有的输入和输出记录都是正确和一致的。 校验通常是基于头和尾进行校验的,校验码和校验算法通常是针对记录的交叉验证。

-

提取应用(Extract Applications): 这个应用程序通常被用来从数据库或者文本文件中读取一系列的记录, 并对记录的选择通常是基于预先确定的规则,然后将这些记录输出到输出文件中。

-

提取/更新应用(Extract/Update Applications): 这个应用程序通常被用来从数据库或者文本文件中读取记录, 并将每一条读取的输入记录更新到数据库或者输出数据库中。

-

处理和更新应用(Processing and Updating Applications): 这种程序对从提取或验证程序 传过来的输入事务记录进行处理。 这处理通常包括有读取数据库并且获得需要处理的数据,为输出处理更新数据库或创建记录。

-

输出和格式化应用(Output/Format Applications): 一个应用通过读取一个输入文件, 对输入文件的结构重新格式化为需要的标准格式,然后创建一个打印的输出文件,或将数据传输到其他的程序或者系统中。

更多的,一个基本的应用外壳应该也能够被针对商业逻辑来提供,这个外壳通常不能通过上面介绍的这些标准模块来完成。

另外的一个主要的构建块,每一个引用通常可以使用下面的一个或者多个标准工具步骤,例如:

-

分类(Sort): 一个程序可以读取输入文件后生成一个输出文件,在这个输出文件中可以对记录进行重新排序, 重新排序的是根据给定记录的关键字段进行重新排序的。分类通常使用标准的系统工具来执行。

-

拆分(Split):一个程序可以读取输入文件后,根据需要的字段值,将输入的文件拆分为多个文件进行输出。拆分通常使用标准的系统工具来执行。

-

合并(Merge):一个程序可以读取多个输入文件,然后将多个输入文件进行合并处理后生成为一个单一的输出文件。 合并可以自定义或者由参数驱动的(parameter-driven)系统实用程序来执行。

批量处理应用程序可以通过下面的输入数据类型来进行分类:

-

数据库驱动应用程序(Database-driven applications)可以通过从数据库中获得的行或值来进行驱动。

-

文件驱动应用程序(File-driven applications) 可以通过从文件中获得的数据来进行驱动。

-

消息驱动应用程序(Message-driven applications) 可以通过从消息队列中获得的数据来进行驱动。

所有批量处理系统的处理基础都是策略(strategy)。对处理策略进行选择产生影响的因素包括有:预估批量处理需要处理的数据量, 在线并发量,和另外一个批量处理系统的在线并发量, 可用的批量处理时间窗口(很多企业都希望系统是能够不间断运行的,基本上来说批量处理可能没有处理时间窗口)。

针对批量处理的标准处理选项包括有(按实现复杂度的递增顺序):

-

在一个批处理窗口中执行常规离线批处理

-

并发批量 / 在线处理

-

并发处理很多不同的批量处理或者有很多批量作业在同一时间运行

-

分区(Partitioning),就是在同一时间有很多示例在运行相同的批量作业

-

混合上面的一些需求

上面的一些选项或者所有选项能够被商业的任务调度所支持。

在下面的部分,我们将会针对上面的处理选项来对细节进行更多的说明。需要特别注意的是, 批量处理程序使用提交和锁定策略将会根据批量处理的不同而有所不同。作为最佳实践,在线锁策略应该使用相同的原则。 因此,在设计批处理整体架构时不能简单地拍脑袋决定,需要进行详细的分析和论证。

锁定策略可以仅仅使用常见的数据库锁或者你也可以在系统架构中使用其他的自定义锁定服务。 这个锁服务将会跟踪数据库的锁(例如在一个专用的数据库表(db-table)中存储必要的信息),然后在应用程序请求数据库操作时授予权限或拒绝。 重试逻辑应该也需要在系统架构中实现,以避免批量作业中的因资源锁定而导致批量任务被终止。

1. 批量处理作业窗口中的常规处理 针对运行在一个单独批处理窗口中的简单批量处理,更新的数据对在线用户或其他批处理来说并没有实时性要求, 也没有并发问题,在批处理运行完成后执行单次提交即可。

大多数情况下,一种更健壮的方法会更合适。要记住的是,批处理系统会随着时间的流逝而增长,包括复杂度和需要处理的数据量。 如果没有合适的锁定策略,系统仍然依赖于一个单一的提交点,则修改批处理程序会是一件痛苦的事情。 因此,即使是最简单的批处理系统, 也应该为重启-恢复(restart-recovery)选项考虑提交逻辑。针对下面的情况,批量处理就更加复杂了。

2. 并发批量 / 在线处理 批处理程序处理的数据如果会同时被在线用户实时更新,就不应该锁定在线用户需要的所有任何数据(不管是数据库还是文件), 即使只需要锁定几秒钟的时间。同时还应该每处理一批事务就提交一次数据库。这减少了其他程序不可用的数据数据量,也压缩了数据不可用的时间。

另一个可以使用的方案就是使用逻辑行基本的锁定实现来替代物理锁定。 通过使用乐观锁(Optimistic Locking )或悲观锁(Pessimistic Locking)模式。

-

乐观锁假设记录争用的可能性很低。这通常意味着并发批处理和在线处理所使用的每个数据表中都有一个时间戳列。 当程序读取一行进行处理时,同时也获得对应的时间戳。当程序处理完该行以后尝试更新时,在 update 操作的 WHERE 子句中使用原来的时间戳作为条件。 如果时间戳相匹配,则数据和时间戳都更新成功。如果时间戳不匹配,这表明在本程序上次获取和此次更新这段时间内已经有另一个程序修改了同一条记录,因此更新不会被执行。

-

悲观锁定策略假设记录争用的可能性很高,因此在检索时需要获得一个物理锁或逻辑锁。有一种悲观逻辑锁在数据表中使用一个专用的 lock-column 列。 当程序想要为更新目的而获取一行时,它在 lock column 上设置一个标志。如果为某一行设置了标志位,其他程序在试图获取同一行时将会逻辑上获取失败。 当设置标志的程序更新该行时,它也同时清除标志位,允许其他程序获取该行。 请注意,在初步获取和初次设置标志位这段时间内必须维护数据的完整性,比如使用数据库锁(例如,SELECT FOR UPDATE)。 还请注意,这种方法和物理锁都有相同的缺点,除了它在构建一个超时机制时比较容易管理。比如记录而用户去吃午餐了,则超时时间到了以后锁会被自动释放。

这些模式并不一定适用于批处理,但他们可以被用在并发批处理和在线处理的情况下(例如,数据库不支持行级锁)。作为一般规则,乐观锁更适合于在线应用, 而悲观锁更适合于批处理应用。只要使用了逻辑锁,那么所有访问逻辑锁保护的数据的程序都必须采用同样的方案。

请注意:这两种解决方案都只锁定(address locking)单条记录。但很多情况下我们需要锁定一组相关的记录。如果使用物理锁,你必须非常小心地管理这些以避免潜在的死锁。 如果使用逻辑锁,通常最好的解决办法是创建一个逻辑锁管理器,使管理器能理解你想要保护的逻辑记录分组(groups),并确保连贯和没有死锁(non-deadlocking)。 这种逻辑锁管理器通常使用其私有的表来进行锁管理、争用报告、超时机制 等等。

3. 并行处理 并行处理允许多个批量处理运行(run)/任务(job)同时并行地运行。以使批量处理总运行时间降到最低。 如果多个任务不使用相同的文件、数据表、索引空间时,批量处理这些不算什么问题。如果确实存在共享和竞争,那么这个服务就应该使用分区数据来实现。 另一种选择是使用控制表来构建一个架构模块以维护他们之间的相互依赖关系。控制表应该为每个共享资源分配一行记录,不管这些资源是否被某个程序所使用。 执行并行作业的批处理架构或程序随后将查询这个控制表,以确定是否可以访问所需的资源。

如果解决了数据访问的问题,并行处理就可以通过使用额外的线程来并行实现。在传统的大型主机环境中,并行作业类上通常被用来确保所有进程都有充足的 CPU 时间。 无论如何,解决方案必须足够强劲,以确保所有正在运行的进程都有足够的运行处理时间。

并行处理的其他关键问题还包括负载平衡以及一般系统资源的可用性(如文件、数据库缓冲池等)。请注意,控制表本身也可能很容易变成一个至关重要的资源(有可能发生严重竞争)。

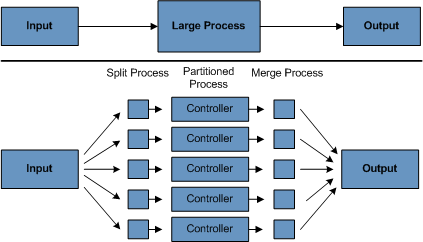

4. 分区 分区技术允许多版本的大型批处理程序并发地(concurrently)运行。这样做的目的是减少超长批处理作业过程所需的时间。 可以成功分区的过程主要是那些可以拆分的输入文件 和/或 主要的数据库表被分区以允许程序使用不同的数据来运行。

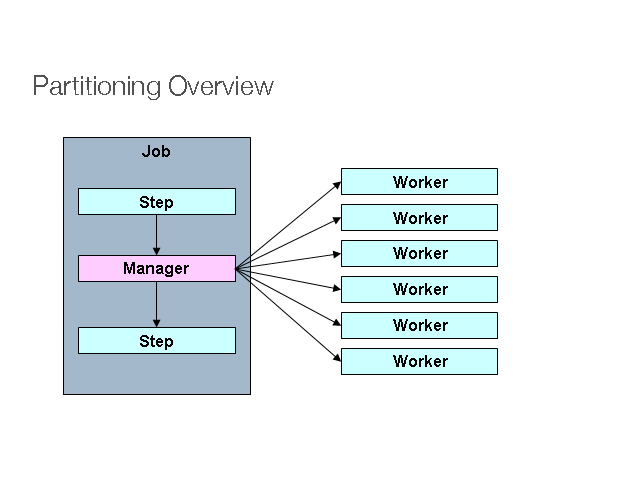

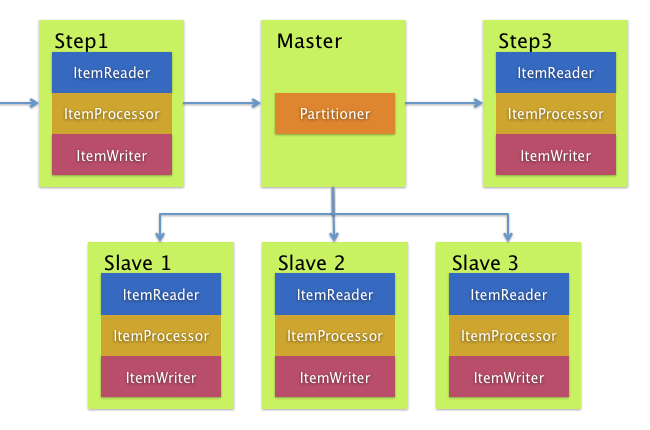

此外,被分区的过程必须设计为只处理分配给他的数据集。分区架构与数据库设计和数据库分区策略是密切相关的。 请注意,数据库分区并不一定指数据库需要在物理上实现分区,尽管在大多数情况下这是明智的。 下面的图片展示了分区的方法:

系统架构应该足够灵活,以允许动态配置分区的数量。自动控制和用户配置都应该纳入考虑范围。 自动配置可以根据参数来决定,例如输入文件大小 和/或 输入记录的数量。

4.1 分区方案 下面列出了一些可能的分区方案,至于具体选择哪种分区方案,要根据具体情况来确定:

1. 固定和均衡拆分记录集

这涉及到将输入的记录集合分解成均衡的部分(例如,拆分为 10 份,这样每部分是整个数据集的十分之一)。 每个拆分的部分稍后由一个批处理/提取程序实例来处理。

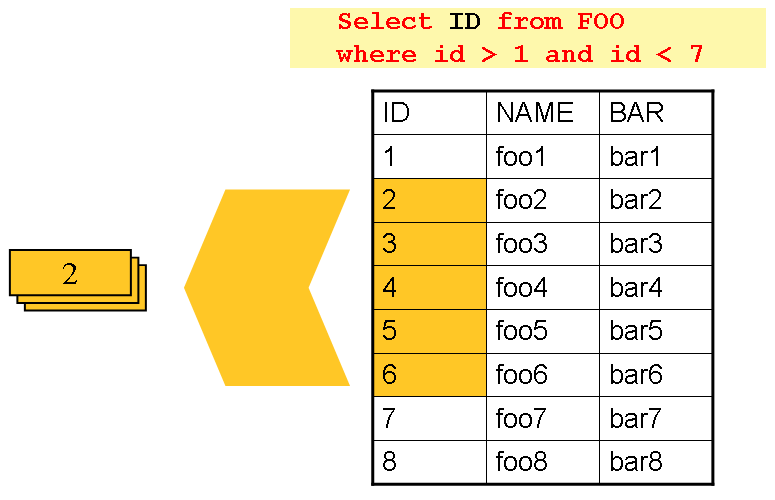

为了使用这种方案,需要在预处理时候就将记录集进行拆分。拆分的结果有一个最大值和最小值的位置,这两个值可以用作限制每个 批处理/提取程序处理部分的输入。

预处理可能有一个很大的开销,因为它必须计算并确定的每部分数据集的边界。

2. 通过关键字段(Key Column)拆分

这涉及到将输入记录按照某个关键字段来拆分,比如一个地区代码(location code),并将每个键分配给一个批处理实例。为了达到这个目标,也可以使用列值:

-

通过分区表来指派给一个批量处理实例。

-

通过值的一部分(例如 0000-0999,1000-1999等)分配给批处理实例。

在选项 1 下,添加新值意味着手动重新配置批处理/提取以确保将新值添加到特定实例。

在选项 2 下,这可确保通过批处理作业的实例覆盖所有值。但是,一个实例处理的值的数量取决于列值的分布(0000-0999范围内可能有大量位置,1000-1999范围内可能很少)。 在此选项下,数据范围应设计为考虑分区。

在这两个选项下,无法实现记录到批处理实例的最佳均匀分布。没有使用批处理实例数的动态配置。

3. 通过视图(Views)

这种方法基本上是根据键列来分解,但不同的是在数据库级进行分解。它涉及到将记录集分解成视图。这些视图将被批处理程序的各个实例在处理时使用。分解将通过数据分组来完成。

使用这个方法时,批处理的每个实例都必须为其配置一个特定的视图(而非主表)。当然,对于新添加的数据,这个新的数据分组必须被包含在某个视图中。 也没有自动配置功能,实例数量的变化将导致视图需要进行相应的改变。

4. 附加的处理识别器

这涉及到输入表一个附加的新列,它充当一个指示器。在预处理阶段,所有指示器都被标志为未处理。在批处理程序获取记录阶段,只会读取被标记为未处理的记录, 一旦他们被读取(并加锁),它们就被标记为正在处理状态。当记录处理完成,指示器将被更新为完成或错误。 批处理程序的多个实例不需要改变就可以开始,因为附加列确保每条纪录只被处理一次。 在“完成时,指标被标记为完成”的顺序中的一两句话。

使用该选项时,表上的I/O会动态地增长。在批量更新的程序中,这种影响被降低了,因为写操作是必定要进行的。

5. 提取表到无格式文件

这包括将表中的数据提取到一个文件中。然后可以将这个文件拆分成多个部分,作为批处理实例的输入。

使用这个选项时,将数据提取到文件中,并将文件拆分的额外开销,有可能抵消多分区处理(multi-partitioning)的效果。可以通过改变文件分割脚本来实现动态配置。

6. 使用哈希列(Hashing Column)

这个计划需要在数据库表中增加一个哈希列(key/index)来检索驱动(driver)记录。这个哈希列将有一个指示器来确定将由批处理程序的哪个实例处理某个特定的行。 例如,如果启动了三个批处理实例,那么 “A” 指示器将标记某行由实例 1 来处理,“B”将标记着将由实例 2 来处理,“C”将标记着将由实例 3 来处理,以此类推。

稍后用于检索记录的过程(procedure)程序,将有一个额外的 WHERE 子句来选择以一个特定指标标记的所有行。 这个表的插入(insert)需要附加的标记字段,默认值将是其中的某一个实例(例如“A”)。

一个简单的批处理程序将被用来更新不同实例之间的重新分配负载的指标。当添加足够多的新行时,这个批处理会被运行(在任何时间,除了在批处理窗口中)。

批处理应用程序的其他实例只需要像上面这样的批处理程序运行着以重新分配指标,以决定新实例的数量。

4.2 数据库和应用设计原则

如果一个支持多分区(multi-partitioned)的应用程序架构,基于数据库采用关键列(key column)分区方法拆成的多个表,则应该包含一个中心分区仓库来存储分区参数。 这种方式提供了灵活性,并保证了可维护性。这个中心仓库通常只由单个表组成,叫做分区表。

存储在分区表中的信息应该是是静态的,并且只能由 DBA 维护。每个多分区程序对应的单个分区有一行记录,组成这个表。 这个表应该包含这些列:程序 ID 编号,分区编号(分区的逻辑ID),一个分区对应的关键列(key column)的最小值,分区对应的关键列的最大值。

在程序启动时,应用程序架构(Control Processing Tasklet, 控制处理微线程)应该将程序 id 和分区号传递给该程序。

这些变量被用于读取分区表,来确定应用程序应该处理的数据范围(如果使用关键列的话)。另外分区号必须在整个处理过程中用来:

-

为了使合并程序正常工作,需要将分区号添加到输出文件/数据库更新

-

向框架的错误处理程序报告正常处理批处理日志和执行期间发生的所有错误

4.3 死锁最小化

当程序并行或分区运行时,会导致数据库资源的争用,还可能会发生死锁(Deadlocks)。其中的关键是数据库设计团队在进行数据库设计时必须考虑尽可能消除潜在的竞争情况。

还要确保设计数据库表的索引时考虑到性能以及死锁预防。

死锁或热点往往发生在管理或架构表上,如日志表、控制表、锁表(lock tables)。这些影响也应该纳入考虑。为了确定架构可能的瓶颈,一个真实的压力测试是至关重要的。

要最小化数据冲突的影响,架构应该提供一些服务,如附加到数据库或遇到死锁时的 等待-重试(wait-and-retry)间隔时间。 这意味着要有一个内置的机制来处理数据库返回码,而不是立即引发错误处理,需要等待一个预定的时间并重试执行数据库操作。

4.4 参数处理和校验

对程序开发人员来说,分区架构应该相对透明。框架以分区模式运行时应该执行的相关任务包括:

-

在程序启动之前获取分区参数

-

在程序启动之前验证分区参数

-

在启动时将参数传递给应用程序

验证(validation)要包含必要的检查,以确保:

-

应用程序已经足够涵盖整个数据的分区

-

在各个分区之间没有遗漏断代(gaps)

如果数据库是分区的,可能需要一些额外的验证来保证单个分区不会跨越数据库的片区。

体系架构应该考虑整合分区(partitions).包括以下关键问题:

-

在进入下一个任务步骤之前是否所有的分区都必须完成?

-

如果一个分区 Job 中止了要怎么处理?

2. Spring Batch 4.2 新特性

Spring Batch 4.2 添加了下面的新特性:

-

使用 Micrometer 来支持批量指标(batch metrics)

-

支持从 Apache Kafka topics 读取/写入(reading/writing) 数据

-

支持从 Apache Avro 资源中读取/写入(reading/writing) 数据

-

改进支持文档

2.1. 使用 Micrometer 的批量指标

本发行版本介绍了可以让你通过使用 Micrometer 来监控你的批量作业。在默认的情况下,Spring Batch 将会收集相关批量指标

(包括,作业时间,步骤的时间,读取和写入的项目,以及其他的相关信息),和将这些指标通过 spring.batch 前缀(prefix)注册到 Micrometer 的全局指标中。

这些指标可以发布到任何能够支持 Micrometer 的 监控系统(monitoring system)中。

有关这个新特性的更多细节,请参考 Monitoring and metrics 章节中的内容。

2.2. Apache Kafka item 读取/写入

本发行版本添加了一个新的 KafkaItemReader 和 KafkaItemWriter, 用来从 Kafka 的 topics 中读取和写入。

有关更多这个新组建的信息,请参考: Javadoc。

2.3. Apache Avro item 读取/写入

本发行版本添加了一个新的 AvroItemReader 和 AvroItemWriter, 用来从 Avro 资源中读取和写入。

有关更多这个新组建的信息,请参考: Javadoc.

3. The Domain Language of Batch

To any experienced batch architect, the overall concepts of batch processing used in

Spring Batch should be familiar and comfortable. There are "Jobs" and "Steps" and

developer-supplied processing units called ItemReader and ItemWriter. However,

because of the Spring patterns, operations, templates, callbacks, and idioms, there are

opportunities for the following:

-

Significant improvement in adherence to a clear separation of concerns.

-

Clearly delineated architectural layers and services provided as interfaces.

-

Simple and default implementations that allow for quick adoption and ease of use out-of-the-box.

-

Significantly enhanced extensibility.

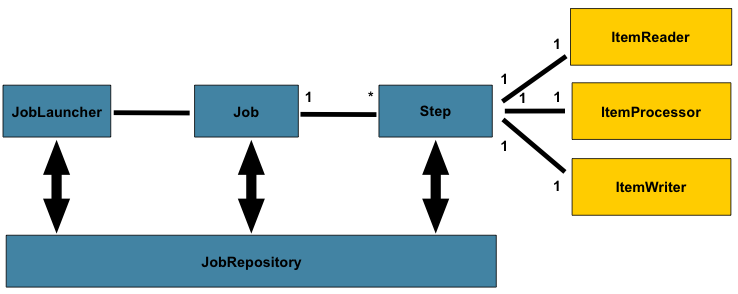

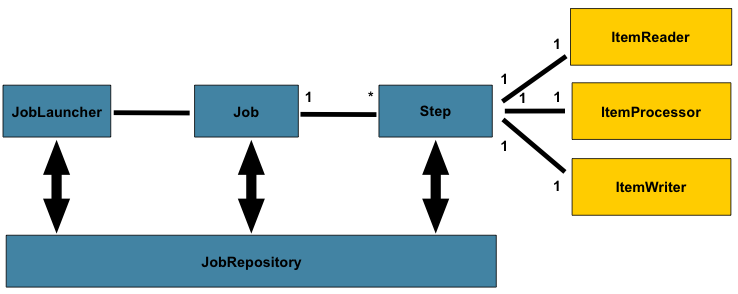

The following diagram is a simplified version of the batch reference architecture that has been used for decades. It provides an overview of the components that make up the domain language of batch processing. This architecture framework is a blueprint that has been proven through decades of implementations on the last several generations of platforms (COBOL/Mainframe, C/Unix, and now Java/anywhere). JCL and COBOL developers are likely to be as comfortable with the concepts as C, C#, and Java developers. Spring Batch provides a physical implementation of the layers, components, and technical services commonly found in the robust, maintainable systems that are used to address the creation of simple to complex batch applications, with the infrastructure and extensions to address very complex processing needs.

The preceding diagram highlights the key concepts that make up the domain language of

Spring Batch. A Job has one to many steps, each of which has exactly one ItemReader,

one ItemProcessor, and one ItemWriter. A job needs to be launched (with

JobLauncher), and metadata about the currently running process needs to be stored (in

JobRepository).

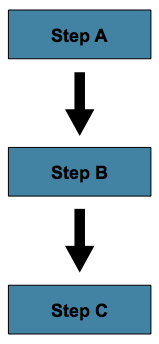

3.1. Job

This section describes stereotypes relating to the concept of a batch job. A Job is an

entity that encapsulates an entire batch process. As is common with other Spring

projects, a Job is wired together with either an XML configuration file or Java-based

configuration. This configuration may be referred to as the "job configuration". However,

Job is just the top of an overall hierarchy, as shown in the following diagram:

In Spring Batch, a Job is simply a container for Step instances. It combines multiple

steps that belong logically together in a flow and allows for configuration of properties

global to all steps, such as restartability. The job configuration contains:

-

The simple name of the job.

-

Definition and ordering of

Stepinstances. -

Whether or not the job is restartable.

A default simple implementation of the Job interface is provided by Spring Batch in the

form of the SimpleJob class, which creates some standard functionality on top of Job.

When using java based configuration, a collection of builders is made available for the

instantiation of a Job, as shown in the following example:

@Bean

public Job footballJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("footballJob")

.start(playerLoad())

.next(gameLoad())

.next(playerSummarization())

.end()

.build();

}A default simple implementation of the Job interface is provided by Spring Batch in the

form of the SimpleJob class, which creates some standard functionality on top of Job.

However, the batch namespace abstracts away the need to instantiate it directly. Instead,

the <job> tag can be used as shown in the following example:

<job id="footballJob">

<step id="playerload" next="gameLoad"/>

<step id="gameLoad" next="playerSummarization"/>

<step id="playerSummarization"/>

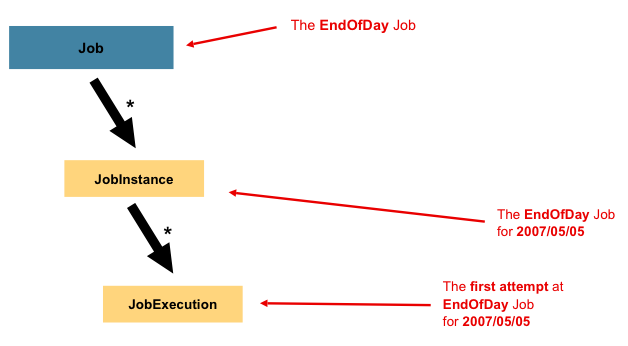

</job>3.1.1. JobInstance

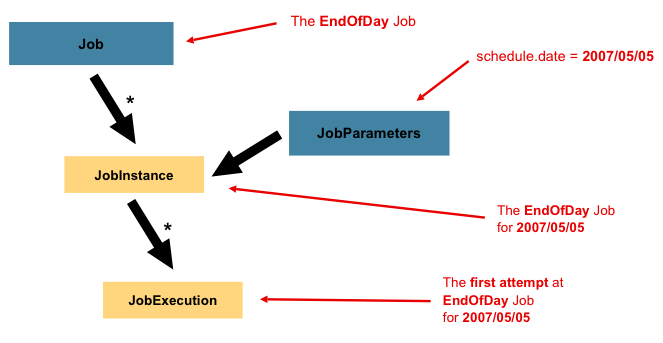

A JobInstance refers to the concept of a logical job run. Consider a batch job that

should be run once at the end of the day, such as the 'EndOfDay' Job from the preceding

diagram. There is one 'EndOfDay' job, but each individual run of the Job must be

tracked separately. In the case of this job, there is one logical JobInstance per day.

For example, there is a January 1st run, a January 2nd run, and so on. If the January 1st

run fails the first time and is run again the next day, it is still the January 1st run.

(Usually, this corresponds with the data it is processing as well, meaning the January

1st run processes data for January 1st). Therefore, each JobInstance can have multiple

executions (JobExecution is discussed in more detail later in this chapter), and only

one JobInstance corresponding to a particular Job and identifying JobParameters can

run at a given time.

The definition of a JobInstance has absolutely no bearing on the data the to be loaded.

It is entirely up to the ItemReader implementation to determine how data is loaded. For

example, in the EndOfDay scenario, there may be a column on the data that indicates the

'effective date' or 'schedule date' to which the data belongs. So, the January 1st run

would load only data from the 1st, and the January 2nd run would use only data from the

2nd. Because this determination is likely to be a business decision, it is left up to the

ItemReader to decide. However, using the same JobInstance determines whether or not

the 'state' (that is, the ExecutionContext, which is discussed later in this chapter)

from previous executions is used. Using a new JobInstance means 'start from the

beginning', and using an existing instance generally means 'start from where you left

off'.

3.1.2. JobParameters

Having discussed JobInstance and how it differs from Job, the natural question to ask

is: "How is one JobInstance distinguished from another?" The answer is:

JobParameters. A JobParameters object holds a set of parameters used to start a batch

job. They can be used for identification or even as reference data during the run, as

shown in the following image:

In the preceding example, where there are two instances, one for January 1st, and another

for January 2nd, there is really only one Job, but it has two JobParameter objects:

one that was started with a job parameter of 01-01-2017 and another that was started with

a parameter of 01-02-2017. Thus, the contract can be defined as: JobInstance = Job

+ identifying JobParameters. This allows a developer to effectively control how a

JobInstance is defined, since they control what parameters are passed in.

Not all job parameters are required to contribute to the identification of a

JobInstance. By default, they do so. However, the framework also allows the submission

of a Job with parameters that do not contribute to the identity of a JobInstance.

|

3.1.3. JobExecution

A JobExecution refers to the technical concept of a single attempt to run a Job. An

execution may end in failure or success, but the JobInstance corresponding to a given

execution is not considered to be complete unless the execution completes successfully.

Using the EndOfDay Job described previously as an example, consider a JobInstance for

01-01-2017 that failed the first time it was run. If it is run again with the same

identifying job parameters as the first run (01-01-2017), a new JobExecution is

created. However, there is still only one JobInstance.

A Job defines what a job is and how it is to be executed, and a JobInstance is a

purely organizational object to group executions together, primarily to enable correct

restart semantics. A JobExecution, however, is the primary storage mechanism for what

actually happened during a run and contains many more properties that must be controlled

and persisted, as shown in the following table:

Property |

Definition |

Status |

A |

startTime |

A |

endTime |

A |

exitStatus |

The |

createTime |

A |

lastUpdated |

A |

executionContext |

The "property bag" containing any user data that needs to be persisted between executions. |

failureExceptions |

The list of exceptions encountered during the execution of a |

These properties are important because they are persisted and can be used to completely determine the status of an execution. For example, if the EndOfDay job for 01-01 is executed at 9:00 PM and fails at 9:30, the following entries are made in the batch metadata tables:

JOB_INST_ID |

JOB_NAME |

1 |

EndOfDayJob |

JOB_EXECUTION_ID |

TYPE_CD |

KEY_NAME |

DATE_VAL |

IDENTIFYING |

1 |

DATE |

schedule.Date |

2017-01-01 |

TRUE |

JOB_EXEC_ID |

JOB_INST_ID |

START_TIME |

END_TIME |

STATUS |

1 |

1 |

2017-01-01 21:00 |

2017-01-01 21:30 |

FAILED |

| Column names may have been abbreviated or removed for the sake of clarity and formatting. |

Now that the job has failed, assume that it took the entire night for the problem to be

determined, so that the 'batch window' is now closed. Further assuming that the window

starts at 9:00 PM, the job is kicked off again for 01-01, starting where it left off and

completing successfully at 9:30. Because it is now the next day, the 01-02 job must be

run as well, and it is kicked off just afterwards at 9:31 and completes in its normal one

hour time at 10:30. There is no requirement that one JobInstance be kicked off after

another, unless there is potential for the two jobs to attempt to access the same data,

causing issues with locking at the database level. It is entirely up to the scheduler to

determine when a Job should be run. Since they are separate JobInstances, Spring

Batch makes no attempt to stop them from being run concurrently. (Attempting to run the

same JobInstance while another is already running results in a

JobExecutionAlreadyRunningException being thrown). There should now be an extra entry

in both the JobInstance and JobParameters tables and two extra entries in the

JobExecution table, as shown in the following tables:

JOB_INST_ID |

JOB_NAME |

1 |

EndOfDayJob |

2 |

EndOfDayJob |

JOB_EXECUTION_ID |

TYPE_CD |

KEY_NAME |

DATE_VAL |

IDENTIFYING |

1 |

DATE |

schedule.Date |

2017-01-01 00:00:00 |

TRUE |

2 |

DATE |

schedule.Date |

2017-01-01 00:00:00 |

TRUE |

3 |

DATE |

schedule.Date |

2017-01-02 00:00:00 |

TRUE |

JOB_EXEC_ID |

JOB_INST_ID |

START_TIME |

END_TIME |

STATUS |

1 |

1 |

2017-01-01 21:00 |

2017-01-01 21:30 |

FAILED |

2 |

1 |

2017-01-02 21:00 |

2017-01-02 21:30 |

COMPLETED |

3 |

2 |

2017-01-02 21:31 |

2017-01-02 22:29 |

COMPLETED |

| Column names may have been abbreviated or removed for the sake of clarity and formatting. |

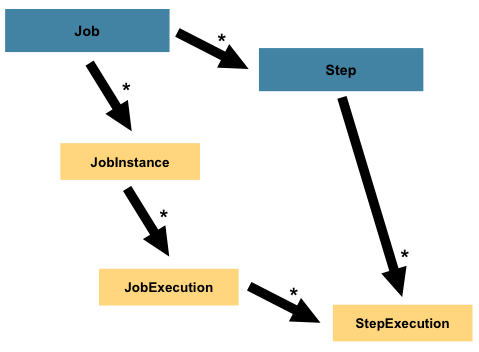

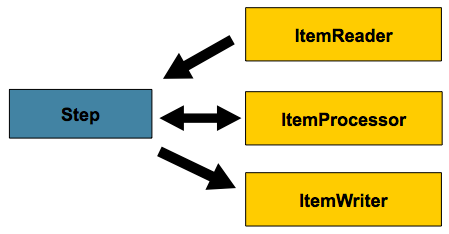

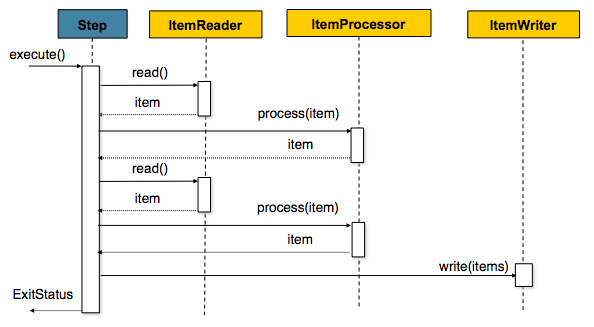

3.2. Step

A Step is a domain object that encapsulates an independent, sequential phase of a batch

job. Therefore, every Job is composed entirely of one or more steps. A Step contains

all of the information necessary to define and control the actual batch processing. This

is a necessarily vague description because the contents of any given Step are at the

discretion of the developer writing a Job. A Step can be as simple or complex as the

developer desires. A simple Step might load data from a file into the database,

requiring little or no code (depending upon the implementations used). A more complex

Step may have complicated business rules that are applied as part of the processing. As

with a Job, a Step has an individual StepExecution that correlates with a unique

JobExecution, as shown in the following image:

3.2.1. StepExecution

A StepExecution represents a single attempt to execute a Step. A new StepExecution

is created each time a Step is run, similar to JobExecution. However, if a step fails

to execute because the step before it fails, no execution is persisted for it. A

StepExecution is created only when its Step is actually started.

Step executions are represented by objects of the StepExecution class. Each execution

contains a reference to its corresponding step and JobExecution and transaction related

data, such as commit and rollback counts and start and end times. Additionally, each step

execution contains an ExecutionContext, which contains any data a developer needs to

have persisted across batch runs, such as statistics or state information needed to

restart. The following table lists the properties for StepExecution:

Property |

Definition |

Status |

A |

startTime |

A |

endTime |

A |

exitStatus |

The |

executionContext |

The "property bag" containing any user data that needs to be persisted between executions. |

readCount |

The number of items that have been successfully read. |

writeCount |

The number of items that have been successfully written. |

commitCount |

The number of transactions that have been committed for this execution. |

rollbackCount |

The number of times the business transaction controlled by the |

readSkipCount |

The number of times |

processSkipCount |

The number of times |

filterCount |

The number of items that have been 'filtered' by the |

writeSkipCount |

The number of times |

3.3. ExecutionContext

An ExecutionContext represents a collection of key/value pairs that are persisted and

controlled by the framework in order to allow developers a place to store persistent

state that is scoped to a StepExecution object or a JobExecution object. For those

familiar with Quartz, it is very similar to JobDataMap. The best usage example is to

facilitate restart. Using flat file input as an example, while processing individual

lines, the framework periodically persists the ExecutionContext at commit points. Doing

so allows the ItemReader to store its state in case a fatal error occurs during the run

or even if the power goes out. All that is needed is to put the current number of lines

read into the context, as shown in the following example, and the framework will do the

rest:

executionContext.putLong(getKey(LINES_READ_COUNT), reader.getPosition());Using the EndOfDay example from the Job Stereotypes section as an example, assume there

is one step, 'loadData', that loads a file into the database. After the first failed run,

the metadata tables would look like the following example:

JOB_INST_ID |

JOB_NAME |

1 |

EndOfDayJob |

JOB_INST_ID |

TYPE_CD |

KEY_NAME |

DATE_VAL |

1 |

DATE |

schedule.Date |

2017-01-01 |

JOB_EXEC_ID |

JOB_INST_ID |

START_TIME |

END_TIME |

STATUS |

1 |

1 |

2017-01-01 21:00 |

2017-01-01 21:30 |

FAILED |

STEP_EXEC_ID |

JOB_EXEC_ID |

STEP_NAME |

START_TIME |

END_TIME |

STATUS |

1 |

1 |

loadData |

2017-01-01 21:00 |

2017-01-01 21:30 |

FAILED |

STEP_EXEC_ID |

SHORT_CONTEXT |

1 |

{piece.count=40321} |

In the preceding case, the Step ran for 30 minutes and processed 40,321 'pieces', which

would represent lines in a file in this scenario. This value is updated just before each

commit by the framework and can contain multiple rows corresponding to entries within the

ExecutionContext. Being notified before a commit requires one of the various

StepListener implementations (or an ItemStream), which are discussed in more detail

later in this guide. As with the previous example, it is assumed that the Job is

restarted the next day. When it is restarted, the values from the ExecutionContext of

the last run are reconstituted from the database. When the ItemReader is opened, it can

check to see if it has any stored state in the context and initialize itself from there,

as shown in the following example:

if (executionContext.containsKey(getKey(LINES_READ_COUNT))) {

log.debug("Initializing for restart. Restart data is: " + executionContext);

long lineCount = executionContext.getLong(getKey(LINES_READ_COUNT));

LineReader reader = getReader();

Object record = "";

while (reader.getPosition() < lineCount && record != null) {

record = readLine();

}

}In this case, after the above code runs, the current line is 40,322, allowing the Step

to start again from where it left off. The ExecutionContext can also be used for

statistics that need to be persisted about the run itself. For example, if a flat file

contains orders for processing that exist across multiple lines, it may be necessary to

store how many orders have been processed (which is much different from the number of

lines read), so that an email can be sent at the end of the Step with the total number

of orders processed in the body. The framework handles storing this for the developer, in

order to correctly scope it with an individual JobInstance. It can be very difficult to

know whether an existing ExecutionContext should be used or not. For example, using the

'EndOfDay' example from above, when the 01-01 run starts again for the second time, the

framework recognizes that it is the same JobInstance and on an individual Step basis,

pulls the ExecutionContext out of the database, and hands it (as part of the

StepExecution) to the Step itself. Conversely, for the 01-02 run, the framework

recognizes that it is a different instance, so an empty context must be handed to the

Step. There are many of these types of determinations that the framework makes for the

developer, to ensure the state is given to them at the correct time. It is also important

to note that exactly one ExecutionContext exists per StepExecution at any given time.

Clients of the ExecutionContext should be careful, because this creates a shared

keyspace. As a result, care should be taken when putting values in to ensure no data is

overwritten. However, the Step stores absolutely no data in the context, so there is no

way to adversely affect the framework.

It is also important to note that there is at least one ExecutionContext per

JobExecution and one for every StepExecution. For example, consider the following

code snippet:

ExecutionContext ecStep = stepExecution.getExecutionContext();

ExecutionContext ecJob = jobExecution.getExecutionContext();

//ecStep does not equal ecJobAs noted in the comment, ecStep does not equal ecJob. They are two different

ExecutionContexts. The one scoped to the Step is saved at every commit point in the

Step, whereas the one scoped to the Job is saved in between every Step execution.

3.4. JobRepository

JobRepository is the persistence mechanism for all of the Stereotypes mentioned above.

It provides CRUD operations for JobLauncher, Job, and Step implementations. When a

Job is first launched, a JobExecution is obtained from the repository, and, during

the course of execution, StepExecution and JobExecution implementations are persisted

by passing them to the repository.

The batch namespace provides support for configuring a JobRepository instance with the

<job-repository> tag, as shown in the following example:

<job-repository id="jobRepository"/>When using java configuration, @EnableBatchProcessing annotation provides a

JobRepository as one of the components automatically configured out of the box.

3.5. JobLauncher

JobLauncher represents a simple interface for launching a Job with a given set of

JobParameters, as shown in the following example:

public interface JobLauncher {

public JobExecution run(Job job, JobParameters jobParameters)

throws JobExecutionAlreadyRunningException, JobRestartException,

JobInstanceAlreadyCompleteException, JobParametersInvalidException;

}It is expected that implementations obtain a valid JobExecution from the

JobRepository and execute the Job.

3.6. Item Reader

ItemReader is an abstraction that represents the retrieval of input for a Step, one

item at a time. When the ItemReader has exhausted the items it can provide, it

indicates this by returning null. More details about the ItemReader interface and its

various implementations can be found in

Readers And Writers.

3.7. Item Writer

ItemWriter is an abstraction that represents the output of a Step, one batch or chunk

of items at a time. Generally, an ItemWriter has no knowledge of the input it should

receive next and knows only the item that was passed in its current invocation. More

details about the ItemWriter interface and its various implementations can be found in

Readers And Writers.

3.8. Item Processor

ItemProcessor is an abstraction that represents the business processing of an item.

While the ItemReader reads one item, and the ItemWriter writes them, the

ItemProcessor provides an access point to transform or apply other business processing.

If, while processing the item, it is determined that the item is not valid, returning

null indicates that the item should not be written out. More details about the

ItemProcessor interface can be found in

Readers And Writers.

3.9. Batch Namespace

Many of the domain concepts listed previously need to be configured in a Spring

ApplicationContext. While there are implementations of the interfaces above that can be

used in a standard bean definition, a namespace has been provided for ease of

configuration, as shown in the following example:

<beans:beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/batch"

xmlns:beans="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="

http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

https://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/batch

https://www.springframework.org/schema/batch/spring-batch.xsd">

<job id="ioSampleJob">

<step id="step1">

<tasklet>

<chunk reader="itemReader" writer="itemWriter" commit-interval="2"/>

</tasklet>

</step>

</job>

</beans:beans>As long as the batch namespace has been declared, any of its elements can be used. More

information on configuring a Job can be found in Configuring and

Running a Job. More information on configuring a Step can be found in

Configuring a Step.

4. Configuring and Running a Job

In the domain section , the overall architecture design was discussed, using the following diagram as a guide:

While the Job object may seem like a simple

container for steps, there are many configuration options of which a

developer must be aware. Furthermore, there are many considerations for

how a Job will be run and how its meta-data will be

stored during that run. This chapter will explain the various configuration

options and runtime concerns of a Job.

4.1. Configuring a Job

There are multiple implementations of the Job interface, however

builders abstract away the difference in configuration.

@Bean

public Job footballJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("footballJob")

.start(playerLoad())

.next(gameLoad())

.next(playerSummarization())

.end()

.build();

}A Job (and typically any Step within it) requires a JobRepository. The

configuration of the JobRepository is handled via the BatchConfigurer.

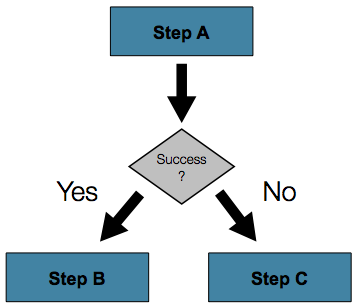

The above example illustrates a Job that consists of three Step instances. The job related

builders can also contain other elements that help with parallelisation (Split),

declarative flow control (Decision) and externalization of flow definitions (Flow).

There are multiple implementations of the Job interface, however, the namespace

abstracts away the differences in configuration. It has only three

required dependencies: a name, a JobRepository , and

a list of Step instances.

<job id="footballJob">

<step id="playerload" parent="s1" next="gameLoad"/>

<step id="gameLoad" parent="s2" next="playerSummarization"/>

<step id="playerSummarization" parent="s3"/>

</job>The examples here use a parent bean definition to create the steps; see the section on step configuration for more options declaring specific step details inline. The XML namespace defaults to referencing a repository with an id of 'jobRepository', which is a sensible default. However, this can be overridden explicitly:

<job id="footballJob" job-repository="specialRepository">

<step id="playerload" parent="s1" next="gameLoad"/>

<step id="gameLoad" parent="s3" next="playerSummarization"/>

<step id="playerSummarization" parent="s3"/>

</job>In addition to steps a job configuration can contain other elements

that help with parallelisation (<split>),

declarative flow control (<decision>) and

externalization of flow definitions

(<flow/>).

4.1.1. Restartability

One key issue when executing a batch job concerns the behavior of

a Job when it is restarted. The launching of a

Job is considered to be a 'restart' if a

JobExecution already exists for the particular

JobInstance. Ideally, all jobs should be able to

start up where they left off, but there are scenarios where this is not

possible. It is entirely up to the developer to ensure that a new JobInstance is created in this scenario. However, Spring Batch does provide some help. If a

Job should never be restarted, but should always

be run as part of a new JobInstance, then the

restartable property may be set to 'false':

<job id="footballJob" restartable="false">

...

</job>@Bean

public Job footballJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("footballJob")

.preventRestart()

...

.build();

}To phrase it another way, setting restartable to false means "this

Job does not support being started again". Restarting a Job that is not

restartable will cause a JobRestartException to

be thrown:

Job job = new SimpleJob();

job.setRestartable(false);

JobParameters jobParameters = new JobParameters();

JobExecution firstExecution = jobRepository.createJobExecution(job, jobParameters);

jobRepository.saveOrUpdate(firstExecution);

try {

jobRepository.createJobExecution(job, jobParameters);

fail();

}

catch (JobRestartException e) {

// expected

}This snippet of JUnit code shows how attempting to create a

JobExecution the first time for a non restartable

job will cause no issues. However, the second

attempt will throw a JobRestartException.

4.1.2. Intercepting Job Execution

During the course of the execution of a

Job, it may be useful to be notified of various

events in its lifecycle so that custom code may be executed. The

SimpleJob allows for this by calling a

JobListener at the appropriate time:

public interface JobExecutionListener {

void beforeJob(JobExecution jobExecution);

void afterJob(JobExecution jobExecution);

}JobListeners can be added to a

SimpleJob via the listeners element on the

job:

<job id="footballJob">

<step id="playerload" parent="s1" next="gameLoad"/>

<step id="gameLoad" parent="s2" next="playerSummarization"/>

<step id="playerSummarization" parent="s3"/>

<listeners>

<listener ref="sampleListener"/>

</listeners>

</job>@Bean

public Job footballJob() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("footballJob")

.listener(sampleListener())

...

.build();

}It should be noted that afterJob will be

called regardless of the success or failure of the

Job. If success or failure needs to be determined

it can be obtained from the JobExecution:

public void afterJob(JobExecution jobExecution){

if( jobExecution.getStatus() == BatchStatus.COMPLETED ){

//job success

}

else if(jobExecution.getStatus() == BatchStatus.FAILED){

//job failure

}

}The annotations corresponding to this interface are:

-

@BeforeJob -

@AfterJob

4.1.3. Inheriting from a Parent Job

If a group of Jobs share similar, but not

identical, configurations, then it may be helpful to define a "parent"

Job from which the concrete

Jobs may inherit properties. Similar to class

inheritance in Java, the "child" Job will combine

its elements and attributes with the parent’s.

In the following example, "baseJob" is an abstract

Job definition that defines only a list of

listeners. The Job "job1" is a concrete

definition that inherits the list of listeners from "baseJob" and merges

it with its own list of listeners to produce a

Job with two listeners and one

Step, "step1".

<job id="baseJob" abstract="true">

<listeners>

<listener ref="listenerOne"/>

<listeners>

</job>

<job id="job1" parent="baseJob">

<step id="step1" parent="standaloneStep"/>

<listeners merge="true">

<listener ref="listenerTwo"/>

<listeners>

</job>Please see the section on Inheriting from a Parent Step for more detailed information.

4.1.4. JobParametersValidator

A job declared in the XML namespace or using any subclass of

AbstractJob can optionally declare a validator for the job parameters at

runtime. This is useful when for instance you need to assert that a job

is started with all its mandatory parameters. There is a

DefaultJobParametersValidator that can be used to constrain combinations

of simple mandatory and optional parameters, and for more complex

constraints you can implement the interface yourself.

The configuration of a validator is supported through the XML namespace through a child element of the job, e.g:

<job id="job1" parent="baseJob3">

<step id="step1" parent="standaloneStep"/>

<validator ref="parametersValidator"/>

</job>The validator can be specified as a reference (as above) or as a nested bean definition in the beans namespace.

The configuration of a validator is supported through the java builders, e.g:

@Bean

public Job job1() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("job1")

.validator(parametersValidator())

...

.build();

}4.2. Java Config

Spring 3 brought the ability to configure applications via java in addition to XML.

As of Spring Batch 2.2.0, batch jobs can be configured using the same

java config. There are two components for the java based configuration:

the @EnableBatchProcessing annotation and two builders.

The @EnableBatchProcessing works similarly to the other

@Enable* annotations in the Spring family. In this case,

@EnableBatchProcessing provides a base configuration for

building batch jobs. Within this base configuration, an instance of

StepScope is created in addition to a number of beans made

available to be autowired:

-

JobRepository- bean name "jobRepository" -

JobLauncher- bean name "jobLauncher" -

JobRegistry- bean name "jobRegistry" -

PlatformTransactionManager- bean name "transactionManager" -

JobBuilderFactory- bean name "jobBuilders" -

StepBuilderFactory- bean name "stepBuilders"

The core interface for this configuration is the BatchConfigurer.

The default implementation provides the beans mentioned above and requires a

DataSource as a bean within the context to be provided. This data

source will be used by the JobRepository. You can customize any of these beans

by creating a custom implementation of the BatchConfigurer interface.

Typically, extending the DefaultBatchConfigurer (which is provided if a

BatchConfigurer is not found) and overriding the required getter is sufficient.

However, implementing your own from scratch may be required. The following

example shows how to provide a custom transaction manager:

@Bean

public BatchConfigurer batchConfigurer() {

return new DefaultBatchConfigurer() {

@Override

public PlatformTransactionManager getTransactionManager() {

return new MyTransactionManager();

}

};

}|

Only one configuration class needs to have the

|

With the base configuration in place, a user can use the provided builder factories

to configure a job. Below is an example of a two step job configured via the

JobBuilderFactory and the StepBuilderFactory.

@Configuration

@EnableBatchProcessing

@Import(DataSourceConfiguration.class)

public class AppConfig {

@Autowired

private JobBuilderFactory jobs;

@Autowired

private StepBuilderFactory steps;

@Bean

public Job job(@Qualifier("step1") Step step1, @Qualifier("step2") Step step2) {

return jobs.get("myJob").start(step1).next(step2).build();

}

@Bean

protected Step step1(ItemReader<Person> reader,

ItemProcessor<Person, Person> processor,

ItemWriter<Person> writer) {

return steps.get("step1")

.<Person, Person> chunk(10)

.reader(reader)

.processor(processor)

.writer(writer)

.build();

}

@Bean

protected Step step2(Tasklet tasklet) {

return steps.get("step2")

.tasklet(tasklet)

.build();

}

}4.3. Configuring a JobRepository

When using @EnableBatchProcessing, a JobRepository is provided out of the box for you.

This section addresses configuring your own.

As described in earlier, the JobRepository is used for basic CRUD operations of the various persisted

domain objects within Spring Batch, such as

JobExecution and

StepExecution. It is required by many of the major

framework features, such as the JobLauncher,

Job, and Step.

The batch

namespace abstracts away many of the implementation details of the

JobRepository implementations and their

collaborators. However, there are still a few configuration options

available:

<job-repository id="jobRepository"

data-source="dataSource"

transaction-manager="transactionManager"

isolation-level-for-create="SERIALIZABLE"

table-prefix="BATCH_"

max-varchar-length="1000"/>None of the configuration options listed above are required except

the id. If they are not set, the defaults shown above will be used. They

are shown above for awareness purposes. The

max-varchar-length defaults to 2500, which is the

length of the long VARCHAR columns in the sample schema scripts

When using java configuration, a JobRepository is provided for you. A JDBC based one is

provided out of the box if a DataSource is provided, the Map based one if not. However

you can customize the configuration of the JobRepository via an implementation of the

BatchConfigurer interface.

...

// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

protected JobRepository createJobRepository() throws Exception {

JobRepositoryFactoryBean factory = new JobRepositoryFactoryBean();

factory.setDataSource(dataSource);

factory.setTransactionManager(transactionManager);

factory.setIsolationLevelForCreate("ISOLATION_SERIALIZABLE");

factory.setTablePrefix("BATCH_");

factory.setMaxVarCharLength(1000);

return factory.getObject();

}

...None of the configuration options listed above are required except

the dataSource and transactionManager. If they are not set, the defaults shown above

will be used. They are shown above for awareness purposes. The

max varchar length defaults to 2500, which is the

length of the long VARCHAR columns in the

sample schema scripts

4.3.1. Transaction Configuration for the JobRepository

If the namespace or the provided FactoryBean is used, transactional advice will be

automatically created around the repository. This is to ensure that the

batch meta data, including state that is necessary for restarts after a

failure, is persisted correctly. The behavior of the framework is not

well defined if the repository methods are not transactional. The

isolation level in the create* method attributes is

specified separately to ensure that when jobs are launched, if two

processes are trying to launch the same job at the same time, only one

will succeed. The default isolation level for that method is

SERIALIZABLE, which is quite aggressive: READ_COMMITTED would work just

as well; READ_UNCOMMITTED would be fine if two processes are not likely

to collide in this way. However, since a call to the

create* method is quite short, it is unlikely

that the SERIALIZED will cause problems, as long as the database

platform supports it. However, this can be overridden:

<job-repository id="jobRepository"

isolation-level-for-create="REPEATABLE_READ" />// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

protected JobRepository createJobRepository() throws Exception {

JobRepositoryFactoryBean factory = new JobRepositoryFactoryBean();

factory.setDataSource(dataSource);

factory.setTransactionManager(transactionManager);

factory.setIsolationLevelForCreate("ISOLATION_REPEATABLE_READ");

return factory.getObject();

}If the namespace or factory beans aren’t used then it is also essential to configure the transactional behavior of the repository using AOP:

<aop:config>

<aop:advisor

pointcut="execution(* org.springframework.batch.core..*Repository+.*(..))"/>

<advice-ref="txAdvice" />

</aop:config>

<tx:advice id="txAdvice" transaction-manager="transactionManager">

<tx:attributes>

<tx:method name="*" />

</tx:attributes>

</tx:advice>This fragment can be used as is, with almost no changes. Remember also to include the appropriate namespace declarations and to make sure spring-tx and spring-aop (or the whole of spring) are on the classpath.

@Bean

public TransactionProxyFactoryBean baseProxy() {

TransactionProxyFactoryBean transactionProxyFactoryBean = new TransactionProxyFactoryBean();

Properties transactionAttributes = new Properties();

transactionAttributes.setProperty("*", "PROPAGATION_REQUIRED");

transactionProxyFactoryBean.setTransactionAttributes(transactionAttributes);

transactionProxyFactoryBean.setTarget(jobRepository());

transactionProxyFactoryBean.setTransactionManager(transactionManager());

return transactionProxyFactoryBean;

}4.3.2. Changing the Table Prefix

Another modifiable property of the

JobRepository is the table prefix of the

meta-data tables. By default they are all prefaced with BATCH_.

BATCH_JOB_EXECUTION and BATCH_STEP_EXECUTION are two examples. However,

there are potential reasons to modify this prefix. If the schema names

needs to be prepended to the table names, or if more than one set of

meta data tables is needed within the same schema, then the table prefix

will need to be changed:

<job-repository id="jobRepository"

table-prefix="SYSTEM.TEST_" />// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

protected JobRepository createJobRepository() throws Exception {

JobRepositoryFactoryBean factory = new JobRepositoryFactoryBean();

factory.setDataSource(dataSource);

factory.setTransactionManager(transactionManager);

factory.setTablePrefix("SYSTEM.TEST_");

return factory.getObject();

}Given the above changes, every query to the meta data tables will be prefixed with "SYSTEM.TEST_". BATCH_JOB_EXECUTION will be referred to as SYSTEM.TEST_JOB_EXECUTION.

|

Only the table prefix is configurable. The table and column names are not. |

4.3.3. In-Memory Repository

There are scenarios in which you may not want to persist your domain objects to the database. One reason may be speed; storing domain objects at each commit point takes extra time. Another reason may be that you just don’t need to persist status for a particular job. For this reason, Spring batch provides an in-memory Map version of the job repository:

<bean id="jobRepository"

class="org.springframework.batch.core.repository.support.MapJobRepositoryFactoryBean">

<property name="transactionManager" ref="transactionManager"/>

</bean>// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

protected JobRepository createJobRepository() throws Exception {

MapJobRepositoryFactoryBean factory = new MapJobRepositoryFactoryBean();

factory.setTransactionManager(transactionManager);

return factory.getObject();

}Note that the in-memory repository is volatile and so does not

allow restart between JVM instances. It also cannot guarantee that two

job instances with the same parameters are launched simultaneously, and

is not suitable for use in a multi-threaded Job, or a locally

partitioned Step. So use the database version of the repository wherever

you need those features.

However it does require a transaction manager to be defined

because there are rollback semantics within the repository, and because

the business logic might still be transactional (e.g. RDBMS access). For

testing purposes many people find the

ResourcelessTransactionManager useful.

4.3.4. Non-standard Database Types in a Repository

If you are using a database platform that is not in the list of

supported platforms, you may be able to use one of the supported types,

if the SQL variant is close enough. To do this you can use the raw

JobRepositoryFactoryBean instead of the namespace

shortcut and use it to set the database type to the closest

match:

<bean id="jobRepository" class="org...JobRepositoryFactoryBean">

<property name="databaseType" value="db2"/>

<property name="dataSource" ref="dataSource"/>

</bean>// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

protected JobRepository createJobRepository() throws Exception {

JobRepositoryFactoryBean factory = new JobRepositoryFactoryBean();

factory.setDataSource(dataSource);

factory.setDatabaseType("db2");

factory.setTransactionManager(transactionManager);

return factory.getObject();

}(The JobRepositoryFactoryBean tries to

auto-detect the database type from the DataSource

if it is not specified.) The major differences between platforms are

mainly accounted for by the strategy for incrementing primary keys, so

often it might be necessary to override the

incrementerFactory as well (using one of the standard

implementations from the Spring Framework).

If even that doesn’t work, or you are not using an RDBMS, then the

only option may be to implement the various Dao

interfaces that the SimpleJobRepository depends

on and wire one up manually in the normal Spring way.

4.4. Configuring a JobLauncher

When using @EnableBatchProcessing, a JobRegistry is provided out of the box for you.

This section addresses configuring your own.

The most basic implementation of the

JobLauncher interface is the

SimpleJobLauncher. Its only required dependency is

a JobRepository, in order to obtain an

execution:

<bean id="jobLauncher"

class="org.springframework.batch.core.launch.support.SimpleJobLauncher">

<property name="jobRepository" ref="jobRepository" />

</bean>...

// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

protected JobLauncher createJobLauncher() throws Exception {

SimpleJobLauncher jobLauncher = new SimpleJobLauncher();

jobLauncher.setJobRepository(jobRepository);

jobLauncher.afterPropertiesSet();

return jobLauncher;

}

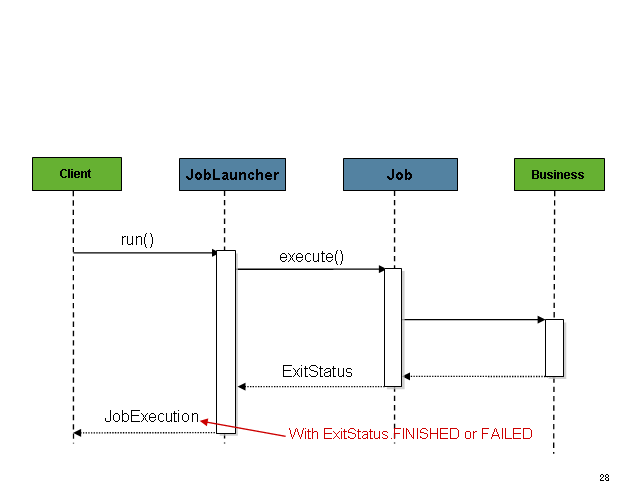

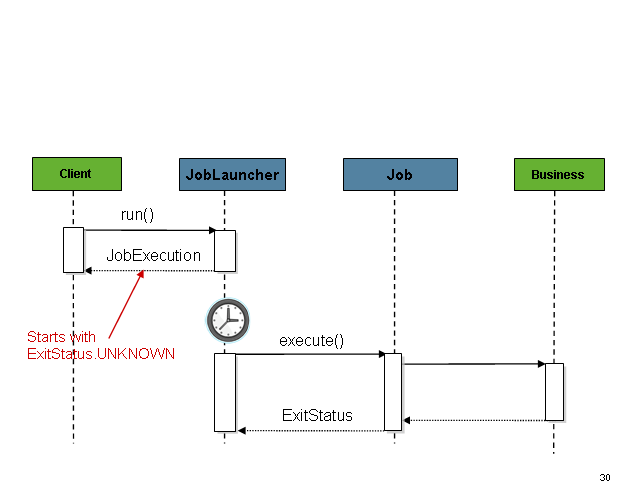

...Once a JobExecution is

obtained, it is passed to the execute method of

Job, ultimately returning the

JobExecution to the caller:

The sequence is straightforward and works well when launched from a

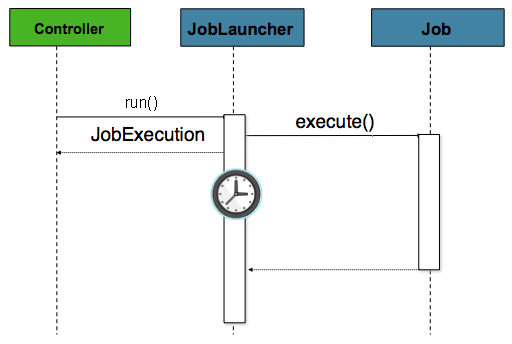

scheduler. However, issues arise when trying to launch from an HTTP

request. In this scenario, the launching needs to be done asynchronously

so that the SimpleJobLauncher returns immediately

to its caller. This is because it is not good practice to keep an HTTP

request open for the amount of time needed by long running processes such

as batch. An example sequence is below:

The SimpleJobLauncher can easily be

configured to allow for this scenario by configuring a

TaskExecutor:

<bean id="jobLauncher"

class="org.springframework.batch.core.launch.support.SimpleJobLauncher">

<property name="jobRepository" ref="jobRepository" />

<property name="taskExecutor">

<bean class="org.springframework.core.task.SimpleAsyncTaskExecutor" />

</property>

</bean>@Bean

public JobLauncher jobLauncher() {

SimpleJobLauncher jobLauncher = new SimpleJobLauncher();

jobLauncher.setJobRepository(jobRepository());

jobLauncher.setTaskExecutor(new SimpleAsyncTaskExecutor());

jobLauncher.afterPropertiesSet();

return jobLauncher;

}Any implementation of the spring TaskExecutor

interface can be used to control how jobs are asynchronously

executed.

4.5. Running a Job

At a minimum, launching a batch job requires two things: the

Job to be launched and a

JobLauncher. Both can be contained within the same

context or different contexts. For example, if launching a job from the

command line, a new JVM will be instantiated for each Job, and thus every

job will have its own JobLauncher. However, if

running from within a web container within the scope of an

HttpRequest, there will usually be one

JobLauncher, configured for asynchronous job

launching, that multiple requests will invoke to launch their jobs.

4.5.1. Running Jobs from the Command Line

For users that want to run their jobs from an enterprise scheduler, the command line is the primary interface. This is because most schedulers (with the exception of Quartz unless using the NativeJob) work directly with operating system processes, primarily kicked off with shell scripts. There are many ways to launch a Java process besides a shell script, such as Perl, Ruby, or even 'build tools' such as ant or maven. However, because most people are familiar with shell scripts, this example will focus on them.

The CommandLineJobRunner

Because the script launching the job must kick off a Java

Virtual Machine, there needs to be a class with a main method to act

as the primary entry point. Spring Batch provides an implementation

that serves just this purpose:

CommandLineJobRunner. It’s important to note

that this is just one way to bootstrap your application, but there are

many ways to launch a Java process, and this class should in no way be

viewed as definitive. The CommandLineJobRunner

performs four tasks:

-

Load the appropriate

ApplicationContext -

Parse command line arguments into

JobParameters -

Locate the appropriate job based on arguments

-

Use the

JobLauncherprovided in the application context to launch the job.

All of these tasks are accomplished using only the arguments passed in. The following are required arguments:

jobPath |

The location of the XML file that will be used to

create an |

jobName |

The name of the job to be run. |

These arguments must be passed in with the path first and the

name second. All arguments after these are considered to be

JobParameters and must be in the format of 'name=value':

<bash$ java CommandLineJobRunner endOfDayJob.xml endOfDay schedule.date(date)=2007/05/05<bash$ java CommandLineJobRunner io.spring.EndOfDayJobConfiguration endOfDay schedule.date(date)=2007/05/05In most cases you would want to use a manifest to declare your

main class in a jar, but for simplicity, the class was used directly.

This example is using the same 'EndOfDay' example from the domainLanguageOfBatch. The first argument is

'endOfDayJob.xml', which is the Spring

ApplicationContext containing the

Job. The second argument, 'endOfDay' represents

the job name. The final argument, 'schedule.date(date)=2007/05/05'

will be converted into JobParameters. An

example of the XML configuration is below:

<job id="endOfDay">

<step id="step1" parent="simpleStep" />

</job>

<!-- Launcher details removed for clarity -->

<beans:bean id="jobLauncher"

class="org.springframework.batch.core.launch.support.SimpleJobLauncher" />In most cases you would want to use a manifest to declare your main class in a jar, but for simplicity, the class was used directly. This example is using the same 'EndOfDay' example from the domainLanguageOfBatch. The first argument is 'io.spring.EndOfDayJobConfiguration', which is the fully qualified class name to the configuration class containing the Job. The second argument, 'endOfDay' represents the job name. The final argument, 'schedule.date(date)=2007/05/05' will be converted into JobParameters. An example of the java configuration is below:

@Configuration

@EnableBatchProcessing

public class EndOfDayJobConfiguration {

@Autowired

private JobBuilderFactory jobBuilderFactory;

@Autowired

private StepBuilderFactory stepBuilderFactory;

@Bean

public Job endOfDay() {

return this.jobBuilderFactory.get("endOfDay")

.start(step1())

.build();

}

@Bean

public Step step1() {

return this.stepBuilderFactory.get("step1")

.tasklet((contribution, chunkContext) -> null)

.build();

}

}This example is overly simplistic, since there are many more

requirements to a run a batch job in Spring Batch in general, but it

serves to show the two main requirements of the

CommandLineJobRunner:

Job and

JobLauncher

ExitCodes

When launching a batch job from the command-line, an enterprise

scheduler is often used. Most schedulers are fairly dumb and work only

at the process level. This means that they only know about some

operating system process such as a shell script that they’re invoking.

In this scenario, the only way to communicate back to the scheduler

about the success or failure of a job is through return codes. A

return code is a number that is returned to a scheduler by the process

that indicates the result of the run. In the simplest case: 0 is

success and 1 is failure. However, there may be more complex

scenarios: If job A returns 4 kick off job B, and if it returns 5 kick

off job C. This type of behavior is configured at the scheduler level,

but it is important that a processing framework such as Spring Batch

provide a way to return a numeric representation of the 'Exit Code'

for a particular batch job. In Spring Batch this is encapsulated

within an ExitStatus, which is covered in more

detail in Chapter 5. For the purposes of discussing exit codes, the

only important thing to know is that an

ExitStatus has an exit code property that is

set by the framework (or the developer) and is returned as part of the

JobExecution returned from the

JobLauncher. The

CommandLineJobRunner converts this string value

to a number using the ExitCodeMapper

interface:

public interface ExitCodeMapper {

public int intValue(String exitCode);

}The essential contract of an

ExitCodeMapper is that, given a string exit

code, a number representation will be returned. The default

implementation used by the job runner is the SimpleJvmExitCodeMapper

that returns 0 for completion, 1 for generic errors, and 2 for any job

runner errors such as not being able to find a

Job in the provided context. If anything more

complex than the 3 values above is needed, then a custom

implementation of the ExitCodeMapper interface

must be supplied. Because the

CommandLineJobRunner is the class that creates

an ApplicationContext, and thus cannot be

'wired together', any values that need to be overwritten must be

autowired. This means that if an implementation of

ExitCodeMapper is found within the BeanFactory,

it will be injected into the runner after the context is created. All

that needs to be done to provide your own

ExitCodeMapper is to declare the implementation

as a root level bean and ensure that it is part of the

ApplicationContext that is loaded by the

runner.

4.5.2. Running Jobs from within a Web Container

Historically, offline processing such as batch jobs have been

launched from the command-line, as described above. However, there are

many cases where launching from an HttpRequest is

a better option. Many such use cases include reporting, ad-hoc job

running, and web application support. Because a batch job by definition

is long running, the most important concern is ensuring to launch the

job asynchronously:

The controller in this case is a Spring MVC controller. More

information on Spring MVC can be found here: https://docs.spring.io/spring/docs/current/spring-framework-reference/web.html#mvc.

The controller launches a Job using a

JobLauncher that has been configured to launch

asynchronously, which

immediately returns a JobExecution. The

Job will likely still be running, however, this

nonblocking behaviour allows the controller to return immediately, which

is required when handling an HttpRequest. An

example is below:

@Controller

public class JobLauncherController {

@Autowired

JobLauncher jobLauncher;

@Autowired

Job job;

@RequestMapping("/jobLauncher.html")

public void handle() throws Exception{

jobLauncher.run(job, new JobParameters());

}

}4.6. Advanced Meta-Data Usage

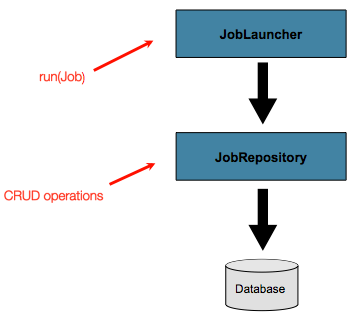

So far, both the JobLauncher and JobRepository interfaces have been

discussed. Together, they represent simple launching of a job, and basic

CRUD operations of batch domain objects:

A JobLauncher uses the

JobRepository to create new

JobExecution objects and run them.

Job and Step implementations

later use the same JobRepository for basic updates

of the same executions during the running of a Job.

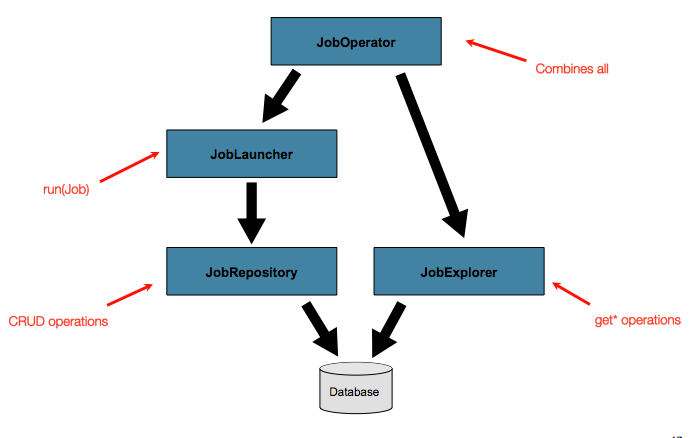

The basic operations suffice for simple scenarios, but in a large batch

environment with hundreds of batch jobs and complex scheduling

requirements, more advanced access of the meta data is required:

The JobExplorer and

JobOperator interfaces, which will be discussed

below, add additional functionality for querying and controlling the meta

data.

4.6.1. Querying the Repository

The most basic need before any advanced features is the ability to

query the repository for existing executions. This functionality is

provided by the JobExplorer interface:

public interface JobExplorer {

List<JobInstance> getJobInstances(String jobName, int start, int count);

JobExecution getJobExecution(Long executionId);

StepExecution getStepExecution(Long jobExecutionId, Long stepExecutionId);

JobInstance getJobInstance(Long instanceId);

List<JobExecution> getJobExecutions(JobInstance jobInstance);

Set<JobExecution> findRunningJobExecutions(String jobName);

}As is evident from the method signatures above,

JobExplorer is a read-only version of the

JobRepository, and like the

JobRepository, it can be easily configured via a

factory bean:

<bean id="jobExplorer" class="org.spr...JobExplorerFactoryBean"

p:dataSource-ref="dataSource" />...

// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

public JobExplorer getJobExplorer() throws Exception {

JobExplorerFactoryBean factoryBean = new JobExplorerFactoryBean();

factoryBean.setDataSource(this.dataSource);

return factoryBean.getObject();

}

...Earlier in this chapter, it was mentioned that the table prefix of the

JobRepository can be modified to allow for

different versions or schemas. Because the

JobExplorer is working with the same tables, it

too needs the ability to set a prefix:

<bean id="jobExplorer" class="org.spr...JobExplorerFactoryBean"

p:tablePrefix="SYSTEM."/>...

// This would reside in your BatchConfigurer implementation

@Override

public JobExplorer getJobExplorer() throws Exception {

JobExplorerFactoryBean factoryBean = new JobExplorerFactoryBean();

factoryBean.setDataSource(this.dataSource);

factoryBean.setTablePrefix("SYSTEM.");

return factoryBean.getObject();

}

...4.6.2. JobRegistry

A JobRegistry (and its parent interface JobLocator) is not

mandatory, but it can be useful if you want to keep track of which jobs

are available in the context. It is also useful for collecting jobs

centrally in an application context when they have been created

elsewhere (e.g. in child contexts). Custom JobRegistry implementations

can also be used to manipulate the names and other properties of the

jobs that are registered. There is only one implementation provided by

the framework and this is based on a simple map from job name to job

instance.

<bean id="jobRegistry" class="org.springframework.batch.core.configuration.support.MapJobRegistry" />When using @EnableBatchProcessing, a JobRegistry is provided out of the box for you.

If you want to configure your own:

...

// This is already provided via the @EnableBatchProcessing but can be customized via

// overriding the getter in the SimpleBatchConfiguration

@Override

@Bean

public JobRegistry jobRegistry() throws Exception {

return new MapJobRegistry();

}

...There are two ways to populate a JobRegistry automatically: using

a bean post processor and using a registrar lifecycle component. These

two mechanisms are described in the following sections.

JobRegistryBeanPostProcessor

This is a bean post-processor that can register all jobs as they are created:

<bean id="jobRegistryBeanPostProcessor" class="org.spr...JobRegistryBeanPostProcessor">

<property name="jobRegistry" ref="jobRegistry"/>

</bean>@Bean

public JobRegistryBeanPostProcessor jobRegistryBeanPostProcessor() {

JobRegistryBeanPostProcessor postProcessor = new JobRegistryBeanPostProcessor();

postProcessor.setJobRegistry(jobRegistry());

return postProcessor;

}Although it is not strictly necessary, the post-processor in the example has been given an id so that it can be included in child contexts (e.g. as a parent bean definition) and cause all jobs created there to also be registered automatically.

AutomaticJobRegistrar

This is a lifecycle component that creates child contexts and

registers jobs from those contexts as they are created. One advantage

of doing this is that, while the job names in the child contexts still

have to be globally unique in the registry, their dependencies can

have "natural" names. So for example, you can create a set of XML

configuration files each having only one Job,

but all having different definitions of an

ItemReader with the same bean name, e.g.

"reader". If all those files were imported into the same context, the

reader definitions would clash and override one another, but with the

automatic registrar this is avoided. This makes it easier to

integrate jobs contributed from separate modules of an

application.

<bean class="org.spr...AutomaticJobRegistrar">

<property name="applicationContextFactories">

<bean class="org.spr...ClasspathXmlApplicationContextsFactoryBean">

<property name="resources" value="classpath*:/config/job*.xml" />

</bean>

</property>

<property name="jobLoader">

<bean class="org.spr...DefaultJobLoader">

<property name="jobRegistry" ref="jobRegistry" />

</bean>

</property>

</bean>@Bean

public AutomaticJobRegistrar registrar() {

AutomaticJobRegistrar registrar = new AutomaticJobRegistrar();

registrar.setJobLoader(jobLoader());

registrar.setApplicationContextFactories(applicationContextFactories());

registrar.afterPropertiesSet();

return registrar;

}The registrar has two mandatory properties, one is an array of

ApplicationContextFactory (here created from a

convenient factory bean), and the other is a

JobLoader. The JobLoader

is responsible for managing the lifecycle of the child contexts and

registering jobs in the JobRegistry.

The ApplicationContextFactory is

responsible for creating the child context and the most common usage

would be as above using a

ClassPathXmlApplicationContextFactory. One of

the features of this factory is that by default it copies some of the

configuration down from the parent context to the child. So for

instance you don’t have to re-define the

PropertyPlaceholderConfigurer or AOP

configuration in the child, if it should be the same as the

parent.

The AutomaticJobRegistrar can be used in

conjunction with a JobRegistryBeanPostProcessor

if desired (as long as the DefaultJobLoader is

used as well). For instance this might be desirable if there are jobs

defined in the main parent context as well as in the child

locations.

4.6.3. JobOperator

As previously discussed, the JobRepository

provides CRUD operations on the meta-data, and the

JobExplorer provides read-only operations on the

meta-data. However, those operations are most useful when used together

to perform common monitoring tasks such as stopping, restarting, or

summarizing a Job, as is commonly done by batch operators. Spring Batch

provides these types of operations via the

JobOperator interface:

public interface JobOperator {

List<Long> getExecutions(long instanceId) throws NoSuchJobInstanceException;

List<Long> getJobInstances(String jobName, int start, int count)

throws NoSuchJobException;

Set<Long> getRunningExecutions(String jobName) throws NoSuchJobException;

String getParameters(long executionId) throws NoSuchJobExecutionException;

Long start(String jobName, String parameters)

throws NoSuchJobException, JobInstanceAlreadyExistsException;

Long restart(long executionId)

throws JobInstanceAlreadyCompleteException, NoSuchJobExecutionException,

NoSuchJobException, JobRestartException;

Long startNextInstance(String jobName)

throws NoSuchJobException, JobParametersNotFoundException, JobRestartException,

JobExecutionAlreadyRunningException, JobInstanceAlreadyCompleteException;

boolean stop(long executionId)

throws NoSuchJobExecutionException, JobExecutionNotRunningException;

String getSummary(long executionId) throws NoSuchJobExecutionException;

Map<Long, String> getStepExecutionSummaries(long executionId)

throws NoSuchJobExecutionException;

Set<String> getJobNames();

}The above operations represent methods from many different

interfaces, such as JobLauncher,

JobRepository,

JobExplorer, and

JobRegistry. For this reason, the provided

implementation of JobOperator,

SimpleJobOperator, has many dependencies:

<bean id="jobOperator" class="org.spr...SimpleJobOperator">

<property name="jobExplorer">

<bean class="org.spr...JobExplorerFactoryBean">

<property name="dataSource" ref="dataSource" />

</bean>

</property>

<property name="jobRepository" ref="jobRepository" />

<property name="jobRegistry" ref="jobRegistry" />

<property name="jobLauncher" ref="jobLauncher" />

</bean> /**

* All injected dependencies for this bean are provided by the @EnableBatchProcessing

* infrastructure out of the box.

*/

@Bean

public SimpleJobOperator jobOperator(JobExplorer jobExplorer,